Edition of 2666 of which 125 copies are signed 1-125, 26 copies are signed A-Z as Artist's Proofs, XX are signed as dedication copies.

Three sets of progressives.

July 30, 2003

8 colors 17-3/8½ x 24½

Client: Berkeley Real Estate Program, Haas School of Business, University of California Berkeley

1-125: Saint Hieronymus Press

Artist's Proofs: Saint Hieronymus Press Dedication copies: Progressives: One set to Steve Chamberlin , two sets reserved to Saint Hieronymus Press.

In 1935 my grandfather was to get the second installment of his soldier's bonus, so he and my grandmother and my mother and her sister went to Grants Pass looking for farmland, where they found that most of the property was selling for sums far greater than they could afford. They bought a newspaper and camped by a gravel bar on the Applegate, and the next day went to a real estate office and were shown property, but none of it suited. The day after that they went to the Illinois Valley, and were shown more land that they didn't like. The agent asked if they would like to accompany her to visit a friend who was just finishing a two storey log house at what is now the Trail's End Motel. The owner said that there was some property for sale next to his place, and took them to look at it. The property had never been cleared, but the soil was good river loam. When grandpa saw it, he said, "This is good ground. I like this place." And they decided on it. There were 143 acres, three acres on the side by the road, and 140 acres across the river. This had been purchased for twenty five thousand dollars by a man who had taken out a school land mortgage on it, but who had been unable to keep up the payments or the taxes, so the land was available for the accumulated taxes. The taxes amounted to $750 for 143 acres, plus a hundred dollars for closing costs and expenses. This was to be paid 85 dollars down and 85 dollars a year for ten years. They didn't have the $85, so the agent forwent her commission until grandpa got his soldier's bonus. The family moved in on April 6th, 1936. Until the fourth of July, they lived across the road in an abandoned school house owned by the man who had introduced them to the property. Grandpa constructed a 6 foot by 12 foot closet, large enough for their clothes and a place to keep their possessions. It had an extension of the roof to cover the cooking area. Cooking was done in a rock fireplace with a sheet iron cover. They started a garden, which was watered from a hand-dug well, and drew water up with a rope attached to my mother's waist. Then grandpa emptied the bucket into a trough made from an oil drum, which was connected by a length of firehose to the garden. Grandma irrigated the garden at the other end. The garden was a success. In August, the bonus came through, and they were able to repay the agent, buy a horse and a cow, a tin can sealer and a pressure cooker. They put up a thousand cans of green beans, prunes and tomatoes that fall, and never could tell what was in what, because the unlabeled cans all looked the same.

In August the real estate agent told grandma there was an opening in the two room school in Fruitdale, two miles out of Grants Pass. She applied and got the position at 75 dollars a month for the four upper grades. Another teacher had the four lower grades. My mother, and her sister Aleta and my grandmother, lived in the house next door to the school all that winter. Grandpa would come in every Friday night and take them home, and return them the 28 miles Sunday evening.

During that year, the widow who owned the adjoining 119 acres offered the property for four thousand dollars, which they did not have, so she came down to three, and then two and finally one thousand. She wanted $250 down and $15 a month. Although that was a good bargain, they didn't have that either, as grandpa was making $36 a month disability pension, and grandma was making $75 a month and paying $30 for rent and food. The widow finally agreed to a down payment of $50 and $15 a month. To raise the down payment, grandma pawned her Auntie May's diamond ring for $40, which was not enough, so her room mate offered to pawn her own diamond ring, and the two together brought $60. The extra ten dollars went for seed that spring. When grandma redeemed the rings and paid the accumulated interest, she made out two checks: one for the principle, and one for the interest, which had been 3% a month. When she was asked why, she said it was so she would always remember how much interest she'd had to pay, and would never do such a thing again.

They found that their first house flooded in the winter, so they built one on the west side of the river. An old barn was there, and grandpa tore it down and used the lumber for the second house. All they had to buy were the windows, and shakes for the roof. Like the first, it was a small house. They had only 25 acres on the east side, all the rest of the property was on the west side. Electric service had not gone as far as the west side, so grandpa took an electric cord and swam across the river with it, giving them electricity in their new home.

The next house was on the east side of the river, but they did not live in it long. Grandpa went to Eugene to find work, and while they were there the house burned. The man who rented it had put a lot of wood and pitch in the stove, and then left the house. One of their children died, and my mother's little dog that had been left there died, and all of their possessions that were stored up in the loft were gone. My grandfather heard about it and got right down, but of course everything was lost, and it was all still smoking, and they'd lost a child in the fire. My mother's sister Aleta died in 1941, at the age of fourteen. Wilda, the second-youngest daughter, had died in 1931 at the age of seven.

During World War Two, having exhausted every means of producing income--raising cattle, berries, chickens--and having gone broke on all of them, grandpa went to Eugene to get work, then to Arizona and Tillamook. Grandma followed along, teaching as she went.

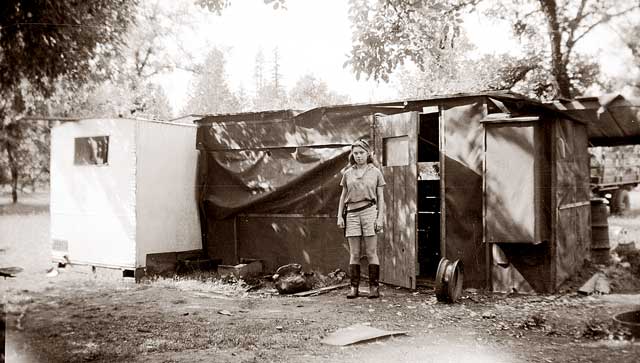

When they returned, two twenty by seventy foot chicken coops were still standing, left over from the chicken breeding failure. One of them became the house, while the other remained a chicken coop. Living under this roof in 1944 were great grandma Peters, my grandmother, Enid, my grandfather, Bill, their daughter Wanda, and her new husband, Warren. My parents spent their wedding night in a tent under a tree near the house. This tree, beneath which I was conceived, stood until 2001, when it was riven by lightning. My parents sold the lumber off for $200.

When I was born, the house had running water, but no indoor toilet. At night, we peed into white enameled-iron thunder mugs, whose lids were decoratively fringed with string doilies worked by great-grandma Peters. Saturday night baths were inflicted in a washtub in the middle of the living room floor, hard by the stove. Littlest ones first, then adults, the water getting colder and dirtier with each use.

Almost every winter it flooded. The house had a high-water mark running three feet off the floor. The ceiling was fitted with heavy hooks, and above the piano was a block and tackle. When the river rose, the piano was hoisted up off the floor until the water went down. One year, when the water was still six inches on the floor, grandpa returned to see a bobcat sitting on the piano. Starving and frightened, it was a menace, so with considerable regret, he shot it.

Coming across the valley you pass deliciously-named watercourses: Crazy Woman Creek, Butcher Knife Creek, Jump Off Joe Creek, until at last you come to the Illinois River, which used to cut through the ranch for a mile on either side but since most of it has been sold off runs along only a quarter mile or so on one side. The great beauty of the property lies in the river. Every year it floods, and changes its shape and depth. Some years the main channel is deep, others find it shallow and swift. Every year it moves around and covers up or uncovers an old wrecked no-color 1938 Buick. When I was little, we would play in it, but it's too beat up and squashed by now to be playable any more.

(Excerpted and adapted from the oral history of Wanda Burch Goines)